Tracking science and innovation policies in response to COVID-19

By Andrés Barreneche

OECD Directorate for Science, Technology and Innovation

21 January, 2021

The COVID-19 pandemic has generated the worst health, economic and social crisis of our lifetime, and the response from governments and science and innovation systems has been unprecedented. As countries continue to grapple with the virus and its fallout, policy makers across the world have recognised that science, technology and innovation (STI) offer the only exit strategy.

Since the start of the crisis, governments have introduced many ambitious STI policy initiatives across a wide range of areas. In the first few months of the pandemic, national research funding bodies spent around USD 5 billion* on emergency funding for R&D to address the virus and its impacts. Thanks to bolstered scientific collaboration and innovative technology, researchers were able to transform the genome of the virus into a successful vaccine in record time. But STI policies extend well beyond the laboratory. Countries have established direct channels for scientific advice to inform policy directives, including when and how to enforce lockdowns and other public health measures. They have also introduced emergency measures to counter the disruption to STI systems, and to support the continuity of public research and business innovation.

The OECD has been tracking such policy efforts since March 2020 and recently launched a new interactive database, the STIP COVID-19 Watch, that provides open access to the data. Developed as part of the STIP Compass, a joint European Commission-OECD project, the portal enables users to build interactive timelines of policy initiatives from more than 40 countries and the European Union (EU). It also features interactive dashboards that allow users to learn more about policy initiatives by country, theme and target group. The database will be regularly updated throughout 2021 as the crisis unfolds.

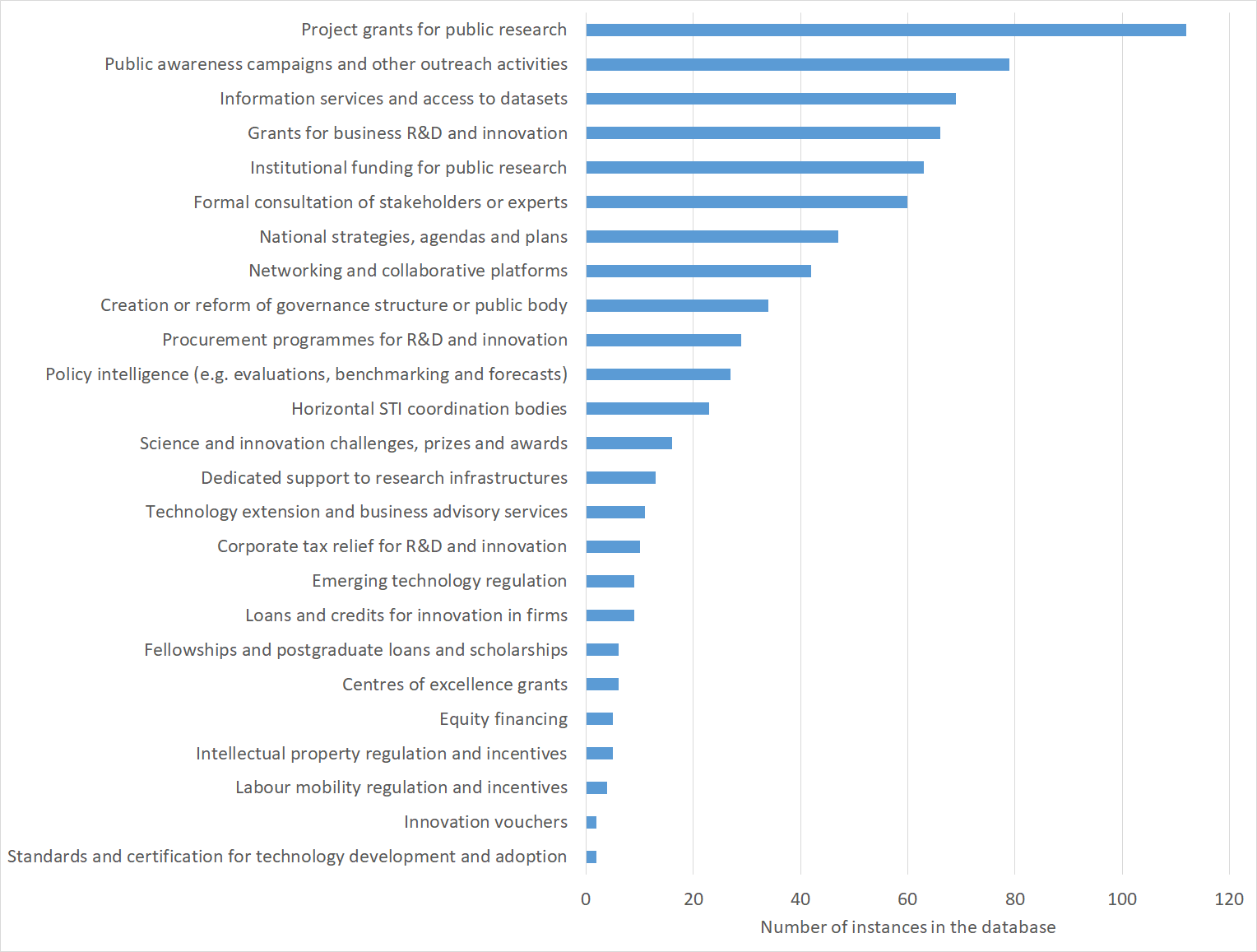

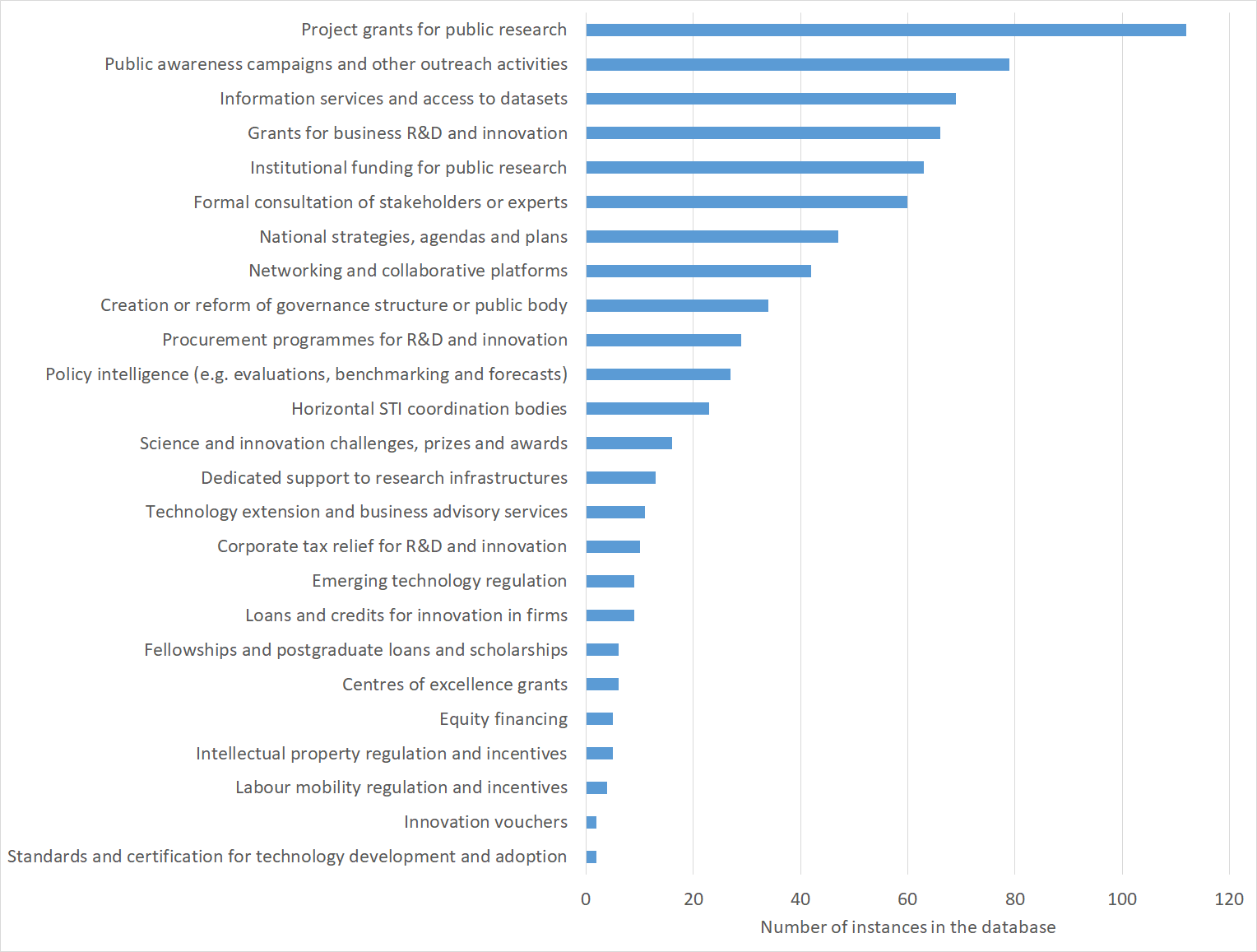

By the end of 2020, almost 700 policies had been reported by government officials in ministries, agencies and public bodies, under the supervision of delegates from the OECD Committee for Scientific and Technological Policy (CSTP). The figure below lists the most frequently used policy instruments, as of January 2021.

Policy instruments reported in the STIP COVID-19 Watch database

Source: STIP COVID-19 Watch, 12 January 2021.

Below are a few more highlights from the information gathered so far:

- Governments from practically all participating countries have together reported more than 200 programmes that provide financial support for public research and infrastructures. These programmes aim to understand and contain the virus, and develop diagnostics, treatments and vaccines. They include, for example, more than EUR 500 million in emergency funds allocated to the United States’ National Institutes of Health (NIH) centres, as well as similar emergency funding measures from countries such as Australia, France, Brazil and the People’s Republic of China. Initiatives supporting public research use a variety of policy instruments, the most common of which are research grants (112 instances in the database), including many fast-tracked grants. In other instances, countries have introduced new institutional funding arrangements or repurposed existing ones to redirect previously allocated resources towards the pandemic (63 instances). These include Germany’s COVID-19 funding for research institutes, the Russian Federation’s additional funding for the prevention and diagnosis of COVID-19 and Canada’s Exceptional Opportunities Fund, to name a few. Other public research initiatives use networking and collaborative platforms or public procurement, among other instruments.

- Thirty countries and the EU reported creating 60 new channels for the formal consultation of stakeholders and experts, as well as 23 horizontal coordination bodies with the primary goals of informing policies with scientific advice and/or coordinating cross-government STI policy responses . The first three months of 2020 saw the creation of various high-level task forces and committees to inform public health responses and introduce immediate socio-economic contingency measures. Later in the year, 14 countries and the EU created similar new channels and bodies aimed at reactivating the economy and implementing recovery plans. Finland, for instance, appointed a high-profile working group to identify ways to strengthen well-being and equality in the aftermath of the crisis; Denmark established an expert group on the long-term health effects of COVID-19; and Spain established a similar multidisciplinary working group to support the Ministry of Science and Innovation in addressing the consequences of the pandemic.

- Thirty-six countries have introduced various measures to support the private sector’s role in combatting the virus and its effects through innovation . These include 40 new business grant schemes for R&D and innovation, 11 new public procurement schemes and six dedicated hackathons . Germany, for instance, launched a Call for Innovative Medicine and Diagnostics Technology for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 and other epidemic infections. Israel introduced a set of grants for start-ups and companies focused on combatting COVID-19 , to be allocated to firms submitting R&D plans, proofs-of-concept, products and technological solutions. New Zealand introduced a COVID-19 Innovation Acceleration Fund for the rapid development and implementation of technologies tackling the disease.

- The database documents at least 38 cases where governments promoted science-industry collaborations to deliver fast and effective solutions, drawing on the combined strengths of the public and private sectors. This includes business and public research grants that jointly target both public and private actors. Poland, for example, created a “ Fast Track Coronavirus” contest that offers financial support to Polish entrepreneurs and scientists, while Sweden launched a call to fund innovative solutions that can be operational within 6 to 12 months, are realised through collaboration, and contribute to a sustainable transition of society, operations and production.

These are only some of the many current policy practices featured on the STIP COVID-19 Watch. The portal provides easy access to international comparative information that contributes to policy learning, helps government officials identify opportunities for international collaboration, and informs related policy research and analysis. For feedback or questions about this interactive database, please reach out at STIPolicy.Data@oecd.org.

---

* In countries for which data was available.

Read more